LARRY DOBY & STEVE GROMEK

It’s Time for MLB to Recognize Larry Doby

U.S. Mint had never made a Congressional Gold Medal like Larry Doby's

Three Is Just a Number

by Mario Crescibene

Feb 15, 2026, 9:09 AM CST

Major League Baseball honors three players with league-wide commemorative days. Larry Doby isn’t one of them. I wanted to know why — despite integrating the American League — MLB refuses to honor Larry Doby with his own day. So I reached out to the Cleveland Guardians and Major League Baseball to find out why.

The Guardians coordinated with MLB and provided an official response:

Major League Baseball has league-wide days for three individual players – Jackie Robinson, Roberto Clemente, and Lou Gehrig. While there are a lot of players who have made an enormous impact on the game both on and off the field, MLB has saved the significant distinction of a league-wide tribute to these three select players. They were selected because:

Jackie was the first player in all of baseball to break the color barrier

Gehrig for his courageous fight against ALS which is still a degenerative disease that MLB and its clubs raise money and awareness for

Clemente, who meant an enormous amount to the community of Latino players and fans. Clemente lost his life in tragic fashion as he was bringing supplies to earthquake victims and as a result, MLB honors him each year with a special day and an award recognizing the social responsibility efforts of its players.

The league response highlighted the ways in which they do honor Doby:

After his retirement, MLB hired Doby where he worked in several capacities… for 13 years (1990-2003), making significant contributions to the office… Major League Baseball has [also] honored Larry Doby by creating the Larry Doby Award which is presented to the MVP of the Futures Game.

The response also pointed out that he is already a highly celebrated legend here in Cleveland:

The Guardians have honored Larry Doby regularly including a statue at Progressive Field, retired number #14, and establishing “Doby Day” playing home annually to honor his debut day July 5, including promotional item giveaways to fans.

From the official response, one thing is abundantly clear: while Cleveland honors Larry Doby, the league he integrated does not. MLB says honoring three players league-wide is enough. Let’s explore Larry Doby’s impact on baseball, and see if he makes a case for a fourth.

Larry Doby integrated the American League in 1947, just eleven weeks after Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier. But those eleven weeks made all the difference in how they were prepared for what was coming.

Jackie Robinson had Branch Rickey — the Dodgers executive who spent years planning integration, who counseled Robinson on what to expect, and built an institutional support system around him. Robinson spent the 1946 season in the minor leagues, learning to handle the pressure and hostility before ever stepping onto a major league field. Larry Doby had none of that. No mentorship. No institutional plan. No preparation period. He was playing in the Negro Leagues one day and in the major leagues the next.

As Doby said:

“Jackie had it better in one way. When he went to spring training in 1946, he had a whole year to get adjusted. I came up in the middle of the season. I was 23 years old, and I had to perform immediately.”

“Nobody showed me the ropes. There was nobody to talk to, nobody to explain what to expect. I was completely alone.”

And when he met his new teammates, it wasn’t with open arms. While Jackie Robinson eventually found allies in the Dodgers clubhouse — teammates like Pee Wee Reese who famously put his arm around Robinson at Crosley Field, publicly showing solidarity — Larry Doby walked into a Cleveland clubhouse that wanted nothing to do with him:

“

Some of the players turned their backs on me, wouldn’t shake my hand. It was a very lonely feeling. Even when you’re on the field, you’re alone.”

“There were some players who wouldn’t room with me, who wouldn’t sit next to me on the bus or in the dugout. I had to overcome that, and it was difficult.”

He received racist treatment as the Indians traveled across the country as well. While his white teammates checked into team hotels, ate at team restaurants, and traveled together, Doby was barred from joining them. Hotels refused him rooms. Restaurants turned him away. In city after city, he had to navigate unfamiliar streets searching for Black neighborhoods where he’d be allowed to sleep and eat. After night games, exhausted from playing, he’d have to find his own lodging — sometimes miles from the ballpark — while his teammates rested comfortably at the team hotel.

“I couldn’t eat with my teammates. I couldn’t stay in the same hotels. I’d have to go find a black family to stay with, or stay in a completely different hotel across town. And then the next day, I was expected to play like nothing was wrong.”

The racist treatment continued for years, but Doby refused to let it break him. In 1948, he hit .301 and helped lead Cleveland to the World Series, where he hit .318 and became the first Black player to hit a home run in a World Series game, propelling Cleveland to their last championship. From 1949 to 1955, he was named an All-Star seven consecutive times, leading the American League in home runs in 1952 and 1954, and in RBIs in 1954. Over his thirteen-year career, Doby compiled a .283 batting average with 253 home runs, 970 RBIs, and 1,533 hits before being inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1998.

His impact extended far beyond his playing days. He became the second Black manager in major league history when he took over the Chicago White Sox in 1978, continuing to break barriers decades after his debut. And in 2023, twenty years after his death, he was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal — one of the nation’s highest civilian honors, recognizing his courage and contributions to American history.

And while he was always being labeled as “the second African American” to play baseball, Larry Doby never let it make him bitter:

“For a while, every time they mentioned me, it was ‘Larry Doby, the second black player.’ I never worried about being second. I just wanted to be treated as a ballplayer, as a human being.”

Larry Doby just wanted to be treated as a ballplayer, as a human being. Major League Baseball should start by treating him like the legend he is. His humility, Hall of Fame career, and groundbreaking legacy demand a league-wide day celebrating his contributions to baseball. Instead, MLB honors him with a minor league award — for a man who never played in the minors. The only thing more absurd than that is claiming there’s logic to their three-player policy. Why three? Is it for three strikes? Three outs? Well there are four balls to a walk, so give Larry Doby his base.

July 5th should be Larry Doby Day league-wide. Every team, every stadium, every player wearing number 14. Because the league he integrated owes him more than a Futures Game trophy.

<

For the front of Doby’s medal, McGraw depicted Doby in Hinchliffe Stadium, the recently restored Paterson, N.J., facility where he starred in high school baseball and football and first tried out for the Negro National League’s Newark Eagles.

U.S. Mint had never made a Congressional Gold Medal like Larry Doby's

February 6th, 2025

Anthony Castrovince

The United States Mint was unaccustomed to requests like the one made by Larry Doby Jr.

For centuries, the bureau of the Department of the Treasury has been responsible for designing and casting the Congressional Gold Medal -- the highest civilian honor in the country. And as part of that process, the Mint’s team of artists will typically consult with recipients or their surviving family members to determine the proper way to present the individual’s achievements and contributions.

But after Congress voted to posthumously award Larry Doby -- a World War II veteran, Negro Leagues star and the first Black player in the American League -- with a Congressional Gold Medal back in 2018,

this process hit a snag.

Because Doby Jr. didn’t just want his father on the coin.

He wanted another man on it, too.

“I was told [by the Mint] right away,” Doby Jr. said, “that that’s not what they do.”

The Mint is not in the habit of emblazoning images of people who aren’t being saluted on these precious medals. Yet Doby Jr. was adamant that the image he requested for the back of the medal was too important to be denied.

If you watch

“Stronger Together,” MLB Network’s new feature on Doby’s Congressional Gold Medal, you’ll see that he was right.

STRONGER TOGETHER

https://youtu.be/C98Qc-o-D7I

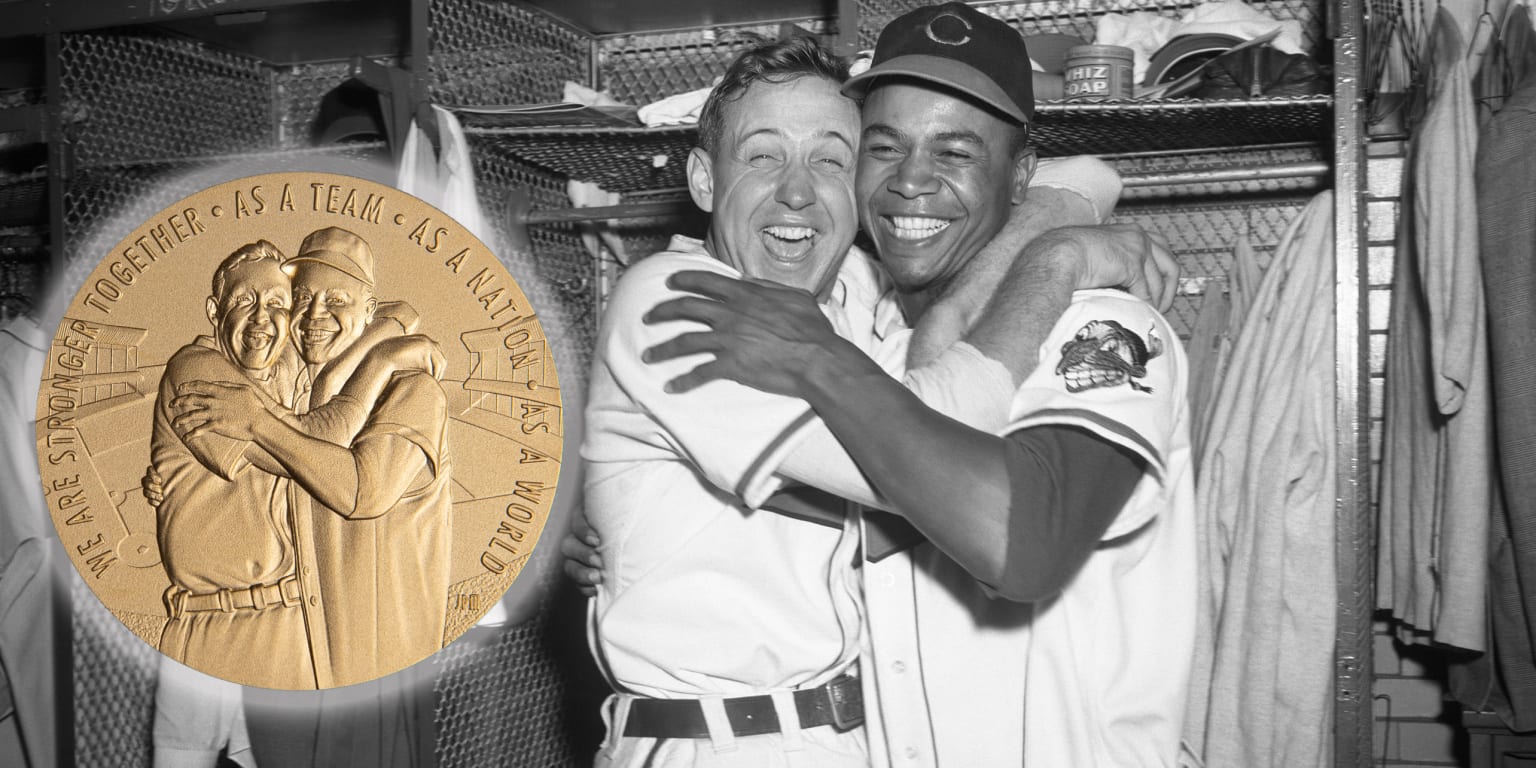

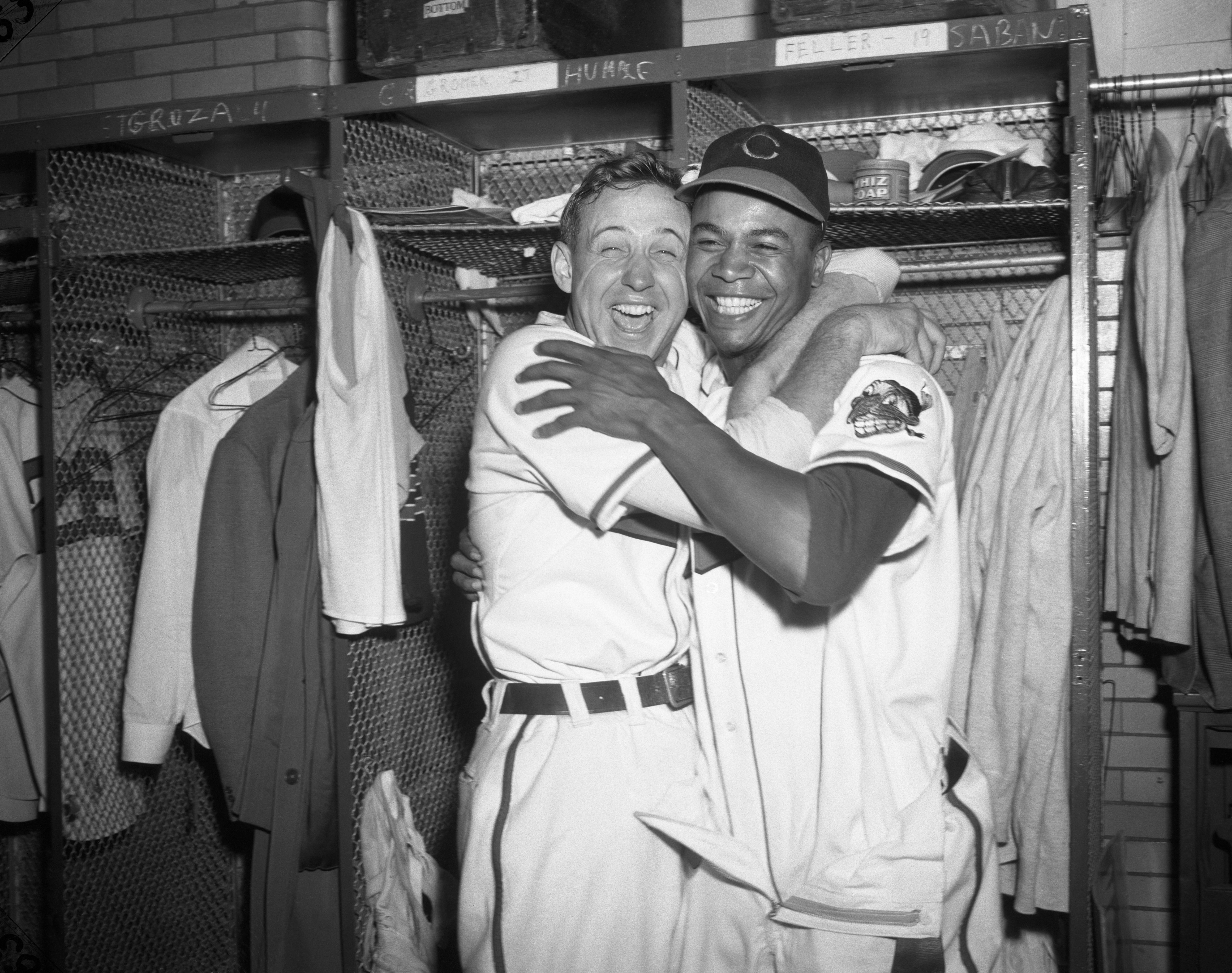

The feature tells the story of a photo taken in the home clubhouse at Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium on Oct. 9, 1948.

That afternoon, in front of more than 80,000 fans, Larry Doby hit the go-ahead home run and a right-hander named Steve Gromek threw a complete game in a 2-1 victory that gave the Indians a commanding lead in a World Series they would go on to win.

In the aftermath, Doby and Gromek embraced, cheek-to-cheek, in front of Gromek’s locker. A Cleveland Plain Dealer photographer snapped the image of the two triumphant teammates, and The Associated Press transmitted it to newspapers across the country. Americans saw a Black man and a white man brandishing big smiles, blissfully unbound by the widespread racial discrimination and segregation of the time.

Some celebrated the photo; many others reflexively cringed.

When Gromek returned home to Hamtramck, Mich., that offseason, he was given the cold shoulder by supposed friends who were angry with him for taking such a photo with a Black man.

“He said that people were put off by it, so they would not engage him in conversation if they bumped into him,” Gromek’s son Carl said of his dad, who passed away in 2002. “But I think my dad looked at it like, ‘They've got a problem, I don't have a problem.’ He cherished that picture.”

So did Doby. He once called it the best moment of his baseball career.

“That is the first time that I can recall -- or many people can recall -- that a Black and a white embraced each other in that fashion, [and it] went all over the world,” said Doby, who passed away in 2003. “That picture just showed to me the feelings that you have. You don’t think about it in terms of color. It’s a feeling you have for a person.”

During the Congressional Gold Medal design process, which typically takes about 18 months even when without holdups, Doby Jr. kept thinking about that photo: What it meant to his dad, what it represented in 1948, and what it represents today.

DOBY JR ON FATHER'S GOLD MEDAL

https://youtu.be/bcUcXt-7wQw

“It’s everything that we should be,” Doby Jr. said. “United, common goal, stronger together.”

Though the Mint’s pushback was an early complication, it was not a lasting one. Doby Jr. was persistent and insistent, even enlisting the help of Rep. Bill Pascrell (D-NJ), who had sponsored the bill that awarded the medal to Doby.

“I guess I dug my heels in a little bit,” Doby Jr. said.

The bureau eventually relented to create what Mint Director Ventris C. Gibson called a “unique” design on the back of Doby’s medal.

“It’s a beautiful image, a milestone image,” said Mint medallic artist John McGraw, the designer of the medal. “It’s also a celebration of Larry Doby being the first Black man to hit a homer in the World Series. To me, as a big baseball fan, I think it’s one of the most important milestones we have in baseball.”

LOU BOUDREAU - LARRY DOBY - HANK GREENBERG

<

LARRY DOBY

1923–2003). In July 1947 hard-hitting Larry Doby became a member of the Cleveland Indians, making him the first African American athlete to play major league baseball in the American League.

Lawrence Eugene Doby was born on Dec. 13, 1923, in Camden, S.C. At the age of 8 he moved to New Jersey with his mother after the death of his father, a semiprofessional baseball player. Doby excelled at many sports during high school. He was all-state in football, basketball, and baseball at Patterson (N.J.) East Side High School and received a basketball scholarship to Long Island University, though he soon transferred to Virginia Union University.

In 1942 Doby began playing baseball with the Newark Eagles of the Negro National League, using the name Larry Walker during his first season in order to protect his amateur status. After a stint in the U.S. Navy, he returned to the team in 1946 and helped them win the Negro League World Series. He was one of only four players to compete in a Negro League World Series and a major league World Series.

While playing second base and hitting .414 during the 1947 season, Doby came to the attention of Bill Veeck, president of the Cleveland Indians. Jackie Robinson had broken major league baseball’s color barrier in April of that year by taking the field with the Brooklyn Dodgers of the National League, but the American League did not have any black players. Veeck purchased Doby’s contract in July 1947. Unlike Robinson, who spent a season with a Dodgers farm club before being called up, Doby immediately jumped into the big leagues, though he primarily served as a pinch-hitter and ended the year with only a .156 batting average. Like Robinson, Doby encountered racism both on and off the field. A quiet man, Doby tended to ignore the injustices and concentrate on his game.

Doby played more frequently in 1948 and found a home in center field. He helped the Indians win the World Series that year by contributing a crucial home run in the fourth game. The following year he played in his first of six consecutive All-Star games. The first black home run champion, the left-handed hitter belted a league-leading 32 home runs in both 1952 and 1954. In the latter year he also led the league in RBIs, with 126.

Doby played with the Chicago White Sox and the Detroit Tigers before his major league career came to a close in 1959. He had a lifetime average of .283 with 253 home runs and 969 runs batted in. After extending his career by playing in Japan, he moved on to coaching duties for various teams. He served as manager of the Chicago White Sox for part of the 1978 season, and he later became a sports administrator.

The Indians retired Doby’s number 14 in 1994. Doby was voted into to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1998. He died on June 18, 2003, in Montclair, N.J.

LARRY DOBY - JACKIE ROBINSON

<