JR, Thank you. Did you get an email from me with a different pic? Did you get that off FB?

This Ipad's copy and paste feature is getting the best of me. I need to get my desktop fixed.

Maybe I will call Apple when I have time. Something could be wrong with it.

Re: Idle Chatter

619JR, you are definitely our go-to guy around here when we have a problem. Hope you know how much appreciated you are.

Did you get my e-mail. I am not sure my mails sent via the IPad are going through. I usually use earthlink's web based program.

Did you get my e-mail. I am not sure my mails sent via the IPad are going through. I usually use earthlink's web based program.

Re: Idle Chatter

622Uncle Dennis wrote: Not Roy Hobbs related, but Cali, is Momma's still on Washington Square next to the Church?

UD, I've never made it, but looks like it is:

http://www.mamas-sf.com/index.html

If I'm in the mood for breakfast out, I know a horse lady who runs a little known diner at the back of the horse barns and near the horse track for workouts down the street from us. If I'm having an omelette out.....and I make pretty good one's on my own.....I normally go to her place to see the horses with my breakfast.

I always remember you touted that place, but the timing has never worked out for my culinary desires while in San Francisco. Maybe during the coming NFL football season when I'm in The City on the way to or from my fave Brown's Bar....

Re: Idle Chatter

623Donna,

Your new Great Grandson looks Great!

And yep, JR is indeed a "go to" guy. I think he knows that he is, but it doesn't hurt to keep buttering him up in case we need him in the future.....

Your new Great Grandson looks Great!

And yep, JR is indeed a "go to" guy. I think he knows that he is, but it doesn't hurt to keep buttering him up in case we need him in the future.....

Re: Idle Chatter

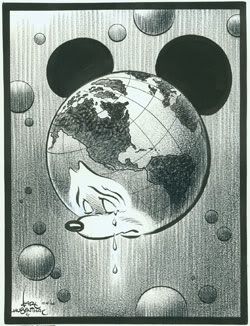

624Oh man, we went to The Walt Disney Family Museum in The Presidio of San Francisco today.

The Presidio is a military complex going back over 200 years that has just within the last 17 years has been converted to civilian profitable use. It's at the southern foot of The Golden Gate Bridge, and fronts The Bay and The Pacific Ocean. A great visit on it's own.

I'm no where near a major Walt Disney fan, especially compared to My Wife and others....including my California Kids.

I did watch The Mickey Mouse Club in it's infancy, and of course the Sunday Disney just before or after Lassie on Sundays as a kid.

I did not expect to linger in this museum for over two hours.....and with a vow afterwards to come back and linger again because I felt I wanted more time.

And darn them, they didn't tell me that the final story exhibit would be Walter Cronkite giving The Country the news on the passing of Walt Disney, and they didn't tell me it would be shown on a mid 60's console TV.

Nor did they tell me in advance that the final large wall of the exhibit would be scores of editorial cartoons from around the World in tribute and sorrow to the passing of Walt Disney in the days later.

They didn't tell me in advance that they were angling to get me misty eyed. Apparently....to my observation.....they didn't tell anyone else either. Few dry eyes at the end.

The Presidio is a military complex going back over 200 years that has just within the last 17 years has been converted to civilian profitable use. It's at the southern foot of The Golden Gate Bridge, and fronts The Bay and The Pacific Ocean. A great visit on it's own.

I'm no where near a major Walt Disney fan, especially compared to My Wife and others....including my California Kids.

I did watch The Mickey Mouse Club in it's infancy, and of course the Sunday Disney just before or after Lassie on Sundays as a kid.

I did not expect to linger in this museum for over two hours.....and with a vow afterwards to come back and linger again because I felt I wanted more time.

And darn them, they didn't tell me that the final story exhibit would be Walter Cronkite giving The Country the news on the passing of Walt Disney, and they didn't tell me it would be shown on a mid 60's console TV.

Nor did they tell me in advance that the final large wall of the exhibit would be scores of editorial cartoons from around the World in tribute and sorrow to the passing of Walt Disney in the days later.

They didn't tell me in advance that they were angling to get me misty eyed. Apparently....to my observation.....they didn't tell anyone else either. Few dry eyes at the end.

Re: Idle Chatter

625Best Chocolate covered French Toast I have ever had! Worth the trip.Tribe Fan in SC/Cali wrote:Uncle Dennis wrote: Not Roy Hobbs related, but Cali, is Momma's still on Washington Square next to the Church?

UD, I've never made it, but looks like it is:

http://www.mamas-sf.com/index.html

If I'm in the mood for breakfast out, I know a horse lady who runs a little known diner at the back of the horse barns and near the horse track for workouts down the street from us. If I'm having an omelette out.....and I make pretty good one's on my own.....I normally go to her place to see the horses with my breakfast.

I always remember you touted that place, but the timing has never worked out for my culinary desires while in San Francisco. Maybe during the coming NFL football season when I'm in The City on the way to or from my fave Brown's Bar....

UD

Re: Idle Chatter

626Film Hitches a Weird Ride on Kesey’s Bus

By CHARLES McGRATH

Published: July 31, 2011

“Magic Trip: Ken Kesey’s Search for a Kool Place,” a film by Alex Gibney and Alison Ellwood that opens on Friday, is an exercise in what they call “archival vérité.” It’s a documentary that uses old footage to recreate a documentary that Kesey intended to make about his 1964 cross-country bus trip — the one so memorably chronicled in Tom Wolfe’s account, “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.”

In all Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, as his crew called themselves, shot some 40 hours of 16-millimeter film, but the project was never really finished. As Mr. Wolfe wrote, “Plunging in on those miles of bouncing, ricocheting, blazing film with a splicer was like entering a jungle where the greeny vines grew faster than you could chop them down in front of you.” Kesey showed all 40 hours unedited a couple of times and also hacked the footage up into various shorter versions before stowing the film cans in his barn, near Eugene, Ore., where they rusted away — until Mr. Gibney and Ms. Ellwood showed up.

Kesey was onto something similar to what we would now call reality television: scenes of people with odd names (Mal Function, Gretchen Fetchin, Generally Famished) getting stoned and behaving weirdly. After publishing the novels “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” and “Sometimes a Great Notion,” he had by 1964 wearied of writing or so fried his brain with hallucinogens that he embraced what he saw as a brand new art form: a drug-enabled psychic quest that would document itself as it was happening. The famous bus — a psychedelic-painted International Harvester with a sign in front that said “Furthur” and one in back that warned “Weird Load” — was wired for sound, and there was a movie camera on board. With Kesey sometimes directing and sometimes just standing back and watching, the Merry Pranksters filmed one another and also their interactions with an uncomprehending public when, for example, Neal Cassady drove the bus backward down a Phoenix street as the Pranksters, stoned on LSD, pretended to campaign for Barry Goldwater for president.

Mr. Gibney, who won an Academy Award for “Taxi to the Dark Side,” his 2007 documentary about American uses of torture during interrogation, and Ms. Ellwood, a film editor who has worked with him on several projects, including “Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room,” first learned of the Kesey footage from a 2004 article in The New Yorker by Robert Stone, who was for a while one of the Pranksters. “That much footage — I thought, wow, what we could do with that,” Mr. Gibney said recently at the Chelsea office of his company, Jigsaw Productions.

But after acquiring the rights from Kesey’s widow (he died in 2001) the filmmakers realized that the footage was in terrible shape, scratched and deteriorating, and first had to be restored. With help from Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation, technicians from the University of California, Los Angeles, worked on it for over a year. And then there was the problem, which took Ms. Ellwood and Don Fleming, an audio expert, several more years to solve, of making sense of a jumble of seemingly random, disconnected reels and snippets where the audio track did not match what was taking place on screen. The recording system was run through a generator on the bus, Mr. Gibney explained, which would unaccountably slow down and speed up.

Nor was anyone operating a clapper to help synchronize the audio and visual tracks. “In 40 hours they used the clapper once,” Mr. Gibney said. “That was in New York when Kesey hired a professional sound man, but he got so frustrated he quit.”

Ms. Ellwood grew so desperate to find moments that synched, she said, that she even hired a lip reader to transcribe what the people were mouthing, in hopes of finding matching audio.

On the other hand Mr. Gibney also found in Kesey’s barn some audiotape recorded about 10 years after the bus trip, in which various Pranksters comment on what’s happening on screen, and this made possible what is probably the most interesting feature of “Magic Trip”: its way of eliminating the talking heads so common in documentaries. There are a few moments of exposition, narrated in mock newsreel style by Stanley Tucci, but for the most part the viewer hears from the participants back when they were still Pranksters more or less and not nostalgic senior citizens.

“We planned to do it the other way,” Mr. Gibney said. “We were going to interview the survivors and intercut those scenes with the original footage. But we found that to be dull, in part because the Pranksters had practiced their stories so many times that to some extent they had ceased to be interested in what the real stories were.”

Ms. Ellwood said, “We thought that if we did it in the traditional way, it would take you off the bus, and we wanted to stay on the bus.”

As edited to under two hours by Mr. Gibney and Ms. Ellwood, the Kesey footage has several memorable scenes, including one in which the novelist Larry McMurtry, whose middle-class house in Houston has just been invaded by Kesey’s band, finds it necessary to call the police and explain that a Prankster, apparently suffering from a drug-induced breakdown, has gone missing and that in keeping with her nickname, Stark Naked, she’s not wearing any clothes.

But there are also long, aimless sequences that seem to take place in druggy slo-mo: Pranksters covering themselves with pond scum; staring raptly at the random designs made by paint swirling in water; tootling interminably on instruments, apparently under the delusion that they sound like John Coltrane. These people are clearly zonked out of their gourds, and so is whoever is holding the camera.

“If you had to watch all 40 hours, it would be like something out of ‘Clockwork Orange,’ ” Mr. Gibney admitted. “They’d have to prop your eyelids open.” He added: “Kesey had an innate distrust of experts: stay away from the experts. In this case that meant stay away from a cameraman. Imagine how great it would have been if they had a real cameraman. But instead you get all the bonehead mistakes of the amateur. There are no establishing shots, the camera is always jiggling, and none of them had a particularly good eye.”

The surprising thing about “Magic Trip” is how sweetly innocent it all seems. The Pranksters are not longhairs. They’re cleanshaven, wear red-white-and-blue outfits and could almost be a patriotic revival group. Most of them too young to be beatniks and too old to be hippies, they have one foot in the ’50s and one in the ’60s.

Kesey, a former college athlete, is blond and muscular and movie-star handsome. He could be Paul Newman’s stand-in. But it’s Cassady, the real-life model for Jack Kerouac’s Dean Moriarty in “On the Road,” who steals the film. He too is buff and magnetically good looking, and while driving he keeps up a nonstop, amphetamine-fueled monologue. Listening to him is so exhausting that the Pranksters have to take turns sitting next to him.

Who in his right mind would travel with such a person at the wheel? And yet blessed by a guardian angel and a mystical GPS in Cassady’s head, the bus navigated flawlessly while Pranksters leaned out from a turret cut in the top or cavorted half-naked on a platform welded to the back.

“They got stopped jillions of times by the police and never got a ticket,” Ms. Ellwood said. “I don’t think Cassady even had a valid driver’s license.

By CHARLES McGRATH

Published: July 31, 2011

“Magic Trip: Ken Kesey’s Search for a Kool Place,” a film by Alex Gibney and Alison Ellwood that opens on Friday, is an exercise in what they call “archival vérité.” It’s a documentary that uses old footage to recreate a documentary that Kesey intended to make about his 1964 cross-country bus trip — the one so memorably chronicled in Tom Wolfe’s account, “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.”

In all Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, as his crew called themselves, shot some 40 hours of 16-millimeter film, but the project was never really finished. As Mr. Wolfe wrote, “Plunging in on those miles of bouncing, ricocheting, blazing film with a splicer was like entering a jungle where the greeny vines grew faster than you could chop them down in front of you.” Kesey showed all 40 hours unedited a couple of times and also hacked the footage up into various shorter versions before stowing the film cans in his barn, near Eugene, Ore., where they rusted away — until Mr. Gibney and Ms. Ellwood showed up.

Kesey was onto something similar to what we would now call reality television: scenes of people with odd names (Mal Function, Gretchen Fetchin, Generally Famished) getting stoned and behaving weirdly. After publishing the novels “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” and “Sometimes a Great Notion,” he had by 1964 wearied of writing or so fried his brain with hallucinogens that he embraced what he saw as a brand new art form: a drug-enabled psychic quest that would document itself as it was happening. The famous bus — a psychedelic-painted International Harvester with a sign in front that said “Furthur” and one in back that warned “Weird Load” — was wired for sound, and there was a movie camera on board. With Kesey sometimes directing and sometimes just standing back and watching, the Merry Pranksters filmed one another and also their interactions with an uncomprehending public when, for example, Neal Cassady drove the bus backward down a Phoenix street as the Pranksters, stoned on LSD, pretended to campaign for Barry Goldwater for president.

Mr. Gibney, who won an Academy Award for “Taxi to the Dark Side,” his 2007 documentary about American uses of torture during interrogation, and Ms. Ellwood, a film editor who has worked with him on several projects, including “Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room,” first learned of the Kesey footage from a 2004 article in The New Yorker by Robert Stone, who was for a while one of the Pranksters. “That much footage — I thought, wow, what we could do with that,” Mr. Gibney said recently at the Chelsea office of his company, Jigsaw Productions.

But after acquiring the rights from Kesey’s widow (he died in 2001) the filmmakers realized that the footage was in terrible shape, scratched and deteriorating, and first had to be restored. With help from Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation, technicians from the University of California, Los Angeles, worked on it for over a year. And then there was the problem, which took Ms. Ellwood and Don Fleming, an audio expert, several more years to solve, of making sense of a jumble of seemingly random, disconnected reels and snippets where the audio track did not match what was taking place on screen. The recording system was run through a generator on the bus, Mr. Gibney explained, which would unaccountably slow down and speed up.

Nor was anyone operating a clapper to help synchronize the audio and visual tracks. “In 40 hours they used the clapper once,” Mr. Gibney said. “That was in New York when Kesey hired a professional sound man, but he got so frustrated he quit.”

Ms. Ellwood grew so desperate to find moments that synched, she said, that she even hired a lip reader to transcribe what the people were mouthing, in hopes of finding matching audio.

On the other hand Mr. Gibney also found in Kesey’s barn some audiotape recorded about 10 years after the bus trip, in which various Pranksters comment on what’s happening on screen, and this made possible what is probably the most interesting feature of “Magic Trip”: its way of eliminating the talking heads so common in documentaries. There are a few moments of exposition, narrated in mock newsreel style by Stanley Tucci, but for the most part the viewer hears from the participants back when they were still Pranksters more or less and not nostalgic senior citizens.

“We planned to do it the other way,” Mr. Gibney said. “We were going to interview the survivors and intercut those scenes with the original footage. But we found that to be dull, in part because the Pranksters had practiced their stories so many times that to some extent they had ceased to be interested in what the real stories were.”

Ms. Ellwood said, “We thought that if we did it in the traditional way, it would take you off the bus, and we wanted to stay on the bus.”

As edited to under two hours by Mr. Gibney and Ms. Ellwood, the Kesey footage has several memorable scenes, including one in which the novelist Larry McMurtry, whose middle-class house in Houston has just been invaded by Kesey’s band, finds it necessary to call the police and explain that a Prankster, apparently suffering from a drug-induced breakdown, has gone missing and that in keeping with her nickname, Stark Naked, she’s not wearing any clothes.

But there are also long, aimless sequences that seem to take place in druggy slo-mo: Pranksters covering themselves with pond scum; staring raptly at the random designs made by paint swirling in water; tootling interminably on instruments, apparently under the delusion that they sound like John Coltrane. These people are clearly zonked out of their gourds, and so is whoever is holding the camera.

“If you had to watch all 40 hours, it would be like something out of ‘Clockwork Orange,’ ” Mr. Gibney admitted. “They’d have to prop your eyelids open.” He added: “Kesey had an innate distrust of experts: stay away from the experts. In this case that meant stay away from a cameraman. Imagine how great it would have been if they had a real cameraman. But instead you get all the bonehead mistakes of the amateur. There are no establishing shots, the camera is always jiggling, and none of them had a particularly good eye.”

The surprising thing about “Magic Trip” is how sweetly innocent it all seems. The Pranksters are not longhairs. They’re cleanshaven, wear red-white-and-blue outfits and could almost be a patriotic revival group. Most of them too young to be beatniks and too old to be hippies, they have one foot in the ’50s and one in the ’60s.

Kesey, a former college athlete, is blond and muscular and movie-star handsome. He could be Paul Newman’s stand-in. But it’s Cassady, the real-life model for Jack Kerouac’s Dean Moriarty in “On the Road,” who steals the film. He too is buff and magnetically good looking, and while driving he keeps up a nonstop, amphetamine-fueled monologue. Listening to him is so exhausting that the Pranksters have to take turns sitting next to him.

Who in his right mind would travel with such a person at the wheel? And yet blessed by a guardian angel and a mystical GPS in Cassady’s head, the bus navigated flawlessly while Pranksters leaned out from a turret cut in the top or cavorted half-naked on a platform welded to the back.

“They got stopped jillions of times by the police and never got a ticket,” Ms. Ellwood said. “I don’t think Cassady even had a valid driver’s license.

" I am not young enough to know everything."

Re: Idle Chatter

628Local history: Akron radio station’s 1966 Beatles ban recalled

Akron’s WAKR not alone in saying band out of line

By Mark J. Price

Beacon Journal staff writer

Published: August 1, 2011 - 12:41 AM

The Beatles

The Beatles

The Beatles (clockwise from top left) Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, John Lennon and George Harrison were banned from Akron's WAKR-AM radio in August 1966.

Americans had enough hot-button issues to keep them preoccupied in August 1966.

In addition to U.S. troop escalation in Vietnam, the nightly news was filled with stories about urban conflagration, civil-rights protestation, nuclear proliferation, women’s liberation and school segregation.

There was always room for one more confrontation.

Namely, teen adulation.

Beatles fans revered Paul McCartney, John Lennon, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. Maybe a little too much.

“WAKR banned the playing of the Beatles records on the station Thursday in light of comments by John Lennon,” Roger G. Berk, vice president and general manager of Akron’s Summit Radio Corp., announced on Aug. 5, 1966. “The ban will continue until such time as it’s in the public interest to play them again.”

As far as the British band was concerned, WAKR’s timing was bloody awful.

That same day, the Beatles released their album Revolver, featuring soon-to-be-classic songs such as Eleanor Rigby, Yellow Submarine, Taxman, Good Day Sunshine and Got to Get You Into My Life.

The Top 40 radio station, whose 1590-AM frequency was advertised as “Top of Your Dial,” ordered disc jockeys Jack Ryan, Wes Hopkins, Randy Davis, Jack Sanders, Ray Robin and Terry Wood to stop spinning Fab Four platters at the Copley Road studio. The boycott was in effect eight days a week.

WAKR was one of 20 U.S. radio stations to pull the plug on the mop-headed musicians after the publication of comments by Lennon that were interpreted as sacrilegious.

In a March 4, 1966, article in the London Evening Standard, Lennon told British interviewer Maureen Cleave:

“Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink. I needn’t argue with that; I’m right and I will be proved right. We’re more popular than Jesus now; I don’t know which will go first — rock ’n’ roll or Christianity. Jesus was all right but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It’s them twisting it that ruins it for me.”

The interview failed to cause a stir in England. It wasn’t until American teen magazine Datebook reprinted an excerpt in July 1966 that all heck broke loose in the United States.

A radio station in Birmingham, Ala., seized on Lennon’s remarks as “absurd and sacrilegious,” and stopped playing Beatles songs. The boycott quickly spread to other stations, which organized public burnings of Beatles records. Ministers accused the Liverpool lads of being “anti-Christ” and warned congregations to steer clear of the unholy band. The Ku Klux Klan nailed Beatles albums to flaming crosses.

Beatles on tour

The controversy erupted as the Beatles prepared for a 14-city tour of North America, including an Aug. 14 stop at Cleveland Municipal Stadium. City officials were willing to give the Beatles another chance after the group’s first visit nearly caused a riot at Public Hall on Sept. 15, 1964. Police halted the concert and whisked the band to safety when hysterical fans stormed the stage.

Cleveland radio station WIXY sponsored the 1966 concert at the stadium: “Rain or shine! Don’t miss this historic show!” Opening acts were the Cyrkle, Bobby Hebb, the Ronettes and the Remains, and tickets cost $3, $4, $5 or $5.50.

Ohio religious leaders, including the Catholic Diocese of Cleveland, urged worshippers to boycott the concert. Although Cleveland’s stadium had 80,000 seats, only 15,000 tickets had been sold a week before the concert.

On the airwaves at WAKR, disc jockeys filled the Beatles void with Napoleon XIV, Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs, Herman’s Hermits and the Troggs. The station conducted nightly polls about the boycott, asking listeners whether Beatles records should be played. Public reaction was mixed.

Some fans tuned to rival Akron station WHLO, which continued to play Beatles records. That Yellow Submarine song was just too catchy to torpedo.

British journalist Cleave, whose article inadvertently led to the Beatles ban, condemned the American controversy as much ado about nothing. She defended Lennon as a spiritual person whose comments were taken out of context by the teen magazine.

“I do not think for one moment that he intended to be flippant or irreverent,” she said. “He was certainly not comparing the Beatles with Christ. He was simply observing that so weak was the state of Christianity that the Beatles were, to many people, better known. He was deploring rather than approving this. Sections of the American public seem to have been given an impression of his views that is totally absurd.”

The Beatles went into damage-control mode. At a news conference Aug. 11 in Chicago, Lennon apologized: “I wasn’t saying whatever they’re saying I was saying. I’m sorry I said it, really.”

He said he was criticizing “false values” among the young people of England, not boasting that the Beatles were “better or greater than Jesus.”

Lennon mused: “If I had said television is more popular than Jesus, I might have got away with it.”

The big show

Nearly 25,000 fans converged on a drizzly Sunday evening at Cleveland’s stadium, the third stop on the tour. More than 55,000 seats were empty at the cavernous home of the Indians and Browns. That’s probably difficult for people to comprehend today. Shouldn’t the Beatles have sold out? If given a second chance today, Beatles fans would fill any stadium to the rafters.

The stage was constructed at second base. About 150 Cleveland police officers kept an eye on the crowd. Although the audience was well-behaved during the opening acts, fans lost control when the Beatles performed.

Ear-splitting screams greeted the band’s set, which included Rock and Roll Music, She’s a Woman, Yesterday, Day Tripper and I Feel Fine. Somewhere around Day Tripper, about 3,000 frenzied fans rushed the stage. Officers tackled teen girls who tried to touch the musicians. The music halted and the band fled to a trailer behind the stage while announcers pleaded with the crowd to return to its seats or the concert would be canceled.

After a 30-minute lull, the band returned to finish the set.

Cleveland fans didn’t know it, but they would never see the band perform live again. Weary of the constant hysteria, the Beatles gave up touring after the North American concerts.

Three days after the Cleveland show, WAKR lifted its ban on Beatles records. The station accepted Lennon’s explanation that his remarks were not meant to be sacrilegious.

“It is the public which will ultimately determine whether the Beatles, or any other recording group, can keep a place in the world of music,” the Akron station announced on Aug. 17, 1966.

The public undoubtedly agreed. WAKR is now an oldies station, and the Beatles are still on the playlist.

Mark J. Price is a Beacon Journal copy editor. He can be reached at 330-996-3850 or send email to mjprice@thebeaconjournal.com.

Akron’s WAKR not alone in saying band out of line

By Mark J. Price

Beacon Journal staff writer

Published: August 1, 2011 - 12:41 AM

The Beatles (clockwise from top left) Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, John Lennon and George Harrison were banned from Akron's WAKR-AM radio in August 1966.

Americans had enough hot-button issues to keep them preoccupied in August 1966.

In addition to U.S. troop escalation in Vietnam, the nightly news was filled with stories about urban conflagration, civil-rights protestation, nuclear proliferation, women’s liberation and school segregation.

There was always room for one more confrontation.

Namely, teen adulation.

Beatles fans revered Paul McCartney, John Lennon, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. Maybe a little too much.

“WAKR banned the playing of the Beatles records on the station Thursday in light of comments by John Lennon,” Roger G. Berk, vice president and general manager of Akron’s Summit Radio Corp., announced on Aug. 5, 1966. “The ban will continue until such time as it’s in the public interest to play them again.”

As far as the British band was concerned, WAKR’s timing was bloody awful.

That same day, the Beatles released their album Revolver, featuring soon-to-be-classic songs such as Eleanor Rigby, Yellow Submarine, Taxman, Good Day Sunshine and Got to Get You Into My Life.

The Top 40 radio station, whose 1590-AM frequency was advertised as “Top of Your Dial,” ordered disc jockeys Jack Ryan, Wes Hopkins, Randy Davis, Jack Sanders, Ray Robin and Terry Wood to stop spinning Fab Four platters at the Copley Road studio. The boycott was in effect eight days a week.

WAKR was one of 20 U.S. radio stations to pull the plug on the mop-headed musicians after the publication of comments by Lennon that were interpreted as sacrilegious.

In a March 4, 1966, article in the London Evening Standard, Lennon told British interviewer Maureen Cleave:

“Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink. I needn’t argue with that; I’m right and I will be proved right. We’re more popular than Jesus now; I don’t know which will go first — rock ’n’ roll or Christianity. Jesus was all right but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It’s them twisting it that ruins it for me.”

The interview failed to cause a stir in England. It wasn’t until American teen magazine Datebook reprinted an excerpt in July 1966 that all heck broke loose in the United States.

A radio station in Birmingham, Ala., seized on Lennon’s remarks as “absurd and sacrilegious,” and stopped playing Beatles songs. The boycott quickly spread to other stations, which organized public burnings of Beatles records. Ministers accused the Liverpool lads of being “anti-Christ” and warned congregations to steer clear of the unholy band. The Ku Klux Klan nailed Beatles albums to flaming crosses.

Beatles on tour

The controversy erupted as the Beatles prepared for a 14-city tour of North America, including an Aug. 14 stop at Cleveland Municipal Stadium. City officials were willing to give the Beatles another chance after the group’s first visit nearly caused a riot at Public Hall on Sept. 15, 1964. Police halted the concert and whisked the band to safety when hysterical fans stormed the stage.

Cleveland radio station WIXY sponsored the 1966 concert at the stadium: “Rain or shine! Don’t miss this historic show!” Opening acts were the Cyrkle, Bobby Hebb, the Ronettes and the Remains, and tickets cost $3, $4, $5 or $5.50.

Ohio religious leaders, including the Catholic Diocese of Cleveland, urged worshippers to boycott the concert. Although Cleveland’s stadium had 80,000 seats, only 15,000 tickets had been sold a week before the concert.

On the airwaves at WAKR, disc jockeys filled the Beatles void with Napoleon XIV, Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs, Herman’s Hermits and the Troggs. The station conducted nightly polls about the boycott, asking listeners whether Beatles records should be played. Public reaction was mixed.

Some fans tuned to rival Akron station WHLO, which continued to play Beatles records. That Yellow Submarine song was just too catchy to torpedo.

British journalist Cleave, whose article inadvertently led to the Beatles ban, condemned the American controversy as much ado about nothing. She defended Lennon as a spiritual person whose comments were taken out of context by the teen magazine.

“I do not think for one moment that he intended to be flippant or irreverent,” she said. “He was certainly not comparing the Beatles with Christ. He was simply observing that so weak was the state of Christianity that the Beatles were, to many people, better known. He was deploring rather than approving this. Sections of the American public seem to have been given an impression of his views that is totally absurd.”

The Beatles went into damage-control mode. At a news conference Aug. 11 in Chicago, Lennon apologized: “I wasn’t saying whatever they’re saying I was saying. I’m sorry I said it, really.”

He said he was criticizing “false values” among the young people of England, not boasting that the Beatles were “better or greater than Jesus.”

Lennon mused: “If I had said television is more popular than Jesus, I might have got away with it.”

The big show

Nearly 25,000 fans converged on a drizzly Sunday evening at Cleveland’s stadium, the third stop on the tour. More than 55,000 seats were empty at the cavernous home of the Indians and Browns. That’s probably difficult for people to comprehend today. Shouldn’t the Beatles have sold out? If given a second chance today, Beatles fans would fill any stadium to the rafters.

The stage was constructed at second base. About 150 Cleveland police officers kept an eye on the crowd. Although the audience was well-behaved during the opening acts, fans lost control when the Beatles performed.

Ear-splitting screams greeted the band’s set, which included Rock and Roll Music, She’s a Woman, Yesterday, Day Tripper and I Feel Fine. Somewhere around Day Tripper, about 3,000 frenzied fans rushed the stage. Officers tackled teen girls who tried to touch the musicians. The music halted and the band fled to a trailer behind the stage while announcers pleaded with the crowd to return to its seats or the concert would be canceled.

After a 30-minute lull, the band returned to finish the set.

Cleveland fans didn’t know it, but they would never see the band perform live again. Weary of the constant hysteria, the Beatles gave up touring after the North American concerts.

Three days after the Cleveland show, WAKR lifted its ban on Beatles records. The station accepted Lennon’s explanation that his remarks were not meant to be sacrilegious.

“It is the public which will ultimately determine whether the Beatles, or any other recording group, can keep a place in the world of music,” the Akron station announced on Aug. 17, 1966.

The public undoubtedly agreed. WAKR is now an oldies station, and the Beatles are still on the playlist.

Mark J. Price is a Beacon Journal copy editor. He can be reached at 330-996-3850 or send email to mjprice@thebeaconjournal.com.

Re: Idle Chatter

629rocky raccoon wrote:Film Hitches a Weird Ride on Kesey’s Bus

Any chance I might catch a glimpse of anyone I know via the internet in that flick?

Re: Idle Chatter

630From Tom Wolfe:

The bus is a superprank. A 1939 International Harvester school bus. The guy that sold it used it for his eleven children. It has bunks, benches, a sink, a refrigerator, shelves, etc. When Ken Kesey buys it for a trip to New York, for the publication of his novel Sometimes a Great Notion, he signs the contract "Intreprid Trips, Inc."

The bus becomes the most outrageous vehicle America has ever seen: shocking painting-job, a hole in the roof to climb up there and sit on the top of the bus, a broadcasting system inside, tapes, microphones, a set of drums, electric guitar, electric bass, huge speakers on top, microphones outside which pick up sounds from the road and broadcast them inside, etc. Weird bus and weird load! The destination sign in the front says, "Furthur"

The bus is driven by Ken Kesey himself or by Neil Cassady, whom Kesey met in San Francisco a few years before. There he is: Neil Cassady! Emerging from On the Road like a myth that has become reality. On acid most of the time. Driving like a maniac. Flipping a sledge hammer during breaks. And the load: "The Merry Pranksters," "Intreprid Travelers," Day-glo crazies (the colour on their bodies), flag people (wrapped in stars and stripes), acid-heads (the drug), hippies (a word not used at that time), Hell’s Angels (at least one of them), drop-outs—people highly elusive of any description!!! And their names and nicknames: Mountain Girl, Black Maria, Doris Delay, Brother John, Kesey’s brother Chuck, Babbs, Hassler, ... and the chief —as Ken Kesey is called.

The bus route: La Honda near San Francisco (Kesey’s place), San Jose (the bus breaks down for the first time), Los Angeles, Wikieup, Arizona, on Route 60 (the first time Acid is distributed among the Pranksters—Authorized Acid only!), Phoenix, Houston (one girl goes mad and gets off the bus), furthur [sic!] down the American Superhighway into the lava (the South in July!), New Orleans (they are almost beaten up by Blacks at Lake Ponchartrain), Alabama, Georgia, the Blue Ridge Mountains (Cassady drives down the mountain highway without using the breaks), and finally, New York: party with Ginsberg,Terry Southern and Kerouac (Kesey, Kerouac, Cassady—and they don’t know what to say to each other!), Sometimes A Great Notion comes out in July 1964, trip to Millbrook, New York, to visit Timothey Leary and the "League for Spititual Discovery," back on the northern route via Calgary to Big Sur (Esalen Institute run by a psychologist named Fritz Perls, the father of the "Now Trip": don’t live in the future or in the past!)

Being on the bus is the main idea. Being on the bus means doing one’s own thing. Apart from that, the meaning of the bus is rather elusive too. Of course, all the action is taped and turned into a movie, but guess what happens to all the material?! No money, no movie! Where are we going? A question that is never asked. Still, there is a common agreement. A current fantasy. "The Unspoken Thing"—quote: "... Cassady pulls the bus off the main road and starts driving up a little mountain road—see where she goes ... they keep climbing and twisting up into nowhere ... It turns out they’re out of gas, which is a nice situation because its nightfall and they’re stranded totally hell west of nowhere with not a gas station within thirty, maybe fifty miles. Nothing to do but stroke themselves out on the bus and go to sleep ... DAWN All wake up to a considerable fetching and hauling and grinding up the grade below them and over the crest comes a CHEVRON gasoline tanker, a huge monster of a tanker. Which just stops like they all met somewhere before and gives them a tankful of gas and without a word heads on into the Sierras toward absolutely NOTHING ... And Kesey—Where does it go? I don’t think man has ever been there. We’re under cosmic control and have been for a long longh time, and each time it builds, it’s bigger, and it’s stronger. And then you find out ... about Cosmo, and you discover that he’s running the show ... (Wolfe, Electric, 111, 112)

Literature on the bus. Yes, they do read a lot. C. G. Jung and his idea that their unconscious receives archertypical signals which make them become microcosmic parts of the whole pattern of the universe. Go and try to see the large pattern! (the tanker!) Go with the flow! Synchronicity! And Hermann Hesse’s The Journey to the East. Hesse describing in 1932 what the Pranksters will do in 1964—quote: "It was like the man had been on acid himself and was on the bus." (Wolfe, Electric, 128). But there are no lectures or seminars. There is no indulging into theories and philosophies. No teacher, no students—all of them are learning. Tuning in to the great flow. Opening their minds. Getting attuned to the principle.

Politics on the bus. The fall of 1965. The Vietnam Day Committee invite Kesey to speak at an anti-war rally at Berkeley. They want the name, they want the author. What they get is a raggamuffin American Army on a bus turned into a tank (the guns and cannons are made of wood), a big American Eagle painted on the bus, and a Ken Kesey dressed in orange wearing a Day-Glo World War I helmet. And the speech he holds is not a speech at all. It’s rather a statement. Kesey playing the harmonica and the Pranksters playing random notes on their instruments. They are doing their thing. Current phantasy. And the audience don’t understand them.

The Dead on the bus. Kesey and Garcia. Jerry Garcia used to hang out with other "lumpenbeatniks" in Palo Alto in the late 50ies. Down and out, dead-end kids. At that time Kesey lived among the intellectuals at Perry Lane, San Francisco. Perry Lane was the Stanford-Bohemian-Intellectual-Scene. Perry Lane was more like a club. Hard to get in. And, well, Jerry Garcia couldn’t get in. The middle-class wine drinkers had to throw him out when he and his friends wanted to crack one of their parties. Now, some years later, Jerry Garcia is a great guitar player and the leader of The Grateful Dead. Legend has it that one night in 1965 psychedelic, electrified rock music is born when the electrified basses and guitars of the Dead meet the flutes, horns, light machines, stroboscope (no, the strobe was not an invention of the disco-people!), and film projectors of the Pranksters in an ancient house rent by Kesey to perform his second big "Acid Test" (how many LSD can you stand without freaking out?). Jazz (named "Warlocks," the Dead played in cheap jazz joints) meets LSD. And the equipment! Quote: "all manner of tuners, amplifiers, receivers, loudspeakers, microphones, cartridges, tapes, theater horns, booms, lights, turntables, instruments, mixers, muters, servile mesochroics, whatever was on the market. The sound went down so many microphones and hooked through so many mixers and variable lags and blew up in so many amplifiers and roiled around in so many speakers and fed back down so many microphones, it came on like a chemical refinery." (Wolfe, Electric, 223)

The bus-bust (trying to outshine Tom Wolfe in terms of alliterations ...). Actually, it is a series of busts. First, Kesey makes it to the front-pages of California. Possession of Marijuana. Kesey, the leader, Kesey, the visionary, Kesey, the saviour. There is some evidence that he gave some pot to minors: 6 months on a work-farm. Second, Kesey is caught smoking Marijuana on a roof. The second offense leads to an automatic 5-year sentence. What a mess! Kesey runs off to Mexico: the fugitive in Puerto Vallarta. A few months later he reenters the U.S. at Brownsville, Texas. Lives as the fugitive for some time in San Francisco. Third, car-chase on a freeway—the cops get him. All in all he gets 90 days in jail and 6 months on the work-farm.

Off the bus. In November 67 Ken Kesey goes back to Springfield, Oregon. Neil Cassady is found dead in Mexico. Drugs and a heart-attack. The Pranksters split up. Various communes. When people come up to Springfield, paying the former chief a visit, they see the bus—it’s still there, parked beside the house.

The bus is a superprank. A 1939 International Harvester school bus. The guy that sold it used it for his eleven children. It has bunks, benches, a sink, a refrigerator, shelves, etc. When Ken Kesey buys it for a trip to New York, for the publication of his novel Sometimes a Great Notion, he signs the contract "Intreprid Trips, Inc."

The bus becomes the most outrageous vehicle America has ever seen: shocking painting-job, a hole in the roof to climb up there and sit on the top of the bus, a broadcasting system inside, tapes, microphones, a set of drums, electric guitar, electric bass, huge speakers on top, microphones outside which pick up sounds from the road and broadcast them inside, etc. Weird bus and weird load! The destination sign in the front says, "Furthur"

The bus is driven by Ken Kesey himself or by Neil Cassady, whom Kesey met in San Francisco a few years before. There he is: Neil Cassady! Emerging from On the Road like a myth that has become reality. On acid most of the time. Driving like a maniac. Flipping a sledge hammer during breaks. And the load: "The Merry Pranksters," "Intreprid Travelers," Day-glo crazies (the colour on their bodies), flag people (wrapped in stars and stripes), acid-heads (the drug), hippies (a word not used at that time), Hell’s Angels (at least one of them), drop-outs—people highly elusive of any description!!! And their names and nicknames: Mountain Girl, Black Maria, Doris Delay, Brother John, Kesey’s brother Chuck, Babbs, Hassler, ... and the chief —as Ken Kesey is called.

The bus route: La Honda near San Francisco (Kesey’s place), San Jose (the bus breaks down for the first time), Los Angeles, Wikieup, Arizona, on Route 60 (the first time Acid is distributed among the Pranksters—Authorized Acid only!), Phoenix, Houston (one girl goes mad and gets off the bus), furthur [sic!] down the American Superhighway into the lava (the South in July!), New Orleans (they are almost beaten up by Blacks at Lake Ponchartrain), Alabama, Georgia, the Blue Ridge Mountains (Cassady drives down the mountain highway without using the breaks), and finally, New York: party with Ginsberg,Terry Southern and Kerouac (Kesey, Kerouac, Cassady—and they don’t know what to say to each other!), Sometimes A Great Notion comes out in July 1964, trip to Millbrook, New York, to visit Timothey Leary and the "League for Spititual Discovery," back on the northern route via Calgary to Big Sur (Esalen Institute run by a psychologist named Fritz Perls, the father of the "Now Trip": don’t live in the future or in the past!)

Being on the bus is the main idea. Being on the bus means doing one’s own thing. Apart from that, the meaning of the bus is rather elusive too. Of course, all the action is taped and turned into a movie, but guess what happens to all the material?! No money, no movie! Where are we going? A question that is never asked. Still, there is a common agreement. A current fantasy. "The Unspoken Thing"—quote: "... Cassady pulls the bus off the main road and starts driving up a little mountain road—see where she goes ... they keep climbing and twisting up into nowhere ... It turns out they’re out of gas, which is a nice situation because its nightfall and they’re stranded totally hell west of nowhere with not a gas station within thirty, maybe fifty miles. Nothing to do but stroke themselves out on the bus and go to sleep ... DAWN All wake up to a considerable fetching and hauling and grinding up the grade below them and over the crest comes a CHEVRON gasoline tanker, a huge monster of a tanker. Which just stops like they all met somewhere before and gives them a tankful of gas and without a word heads on into the Sierras toward absolutely NOTHING ... And Kesey—Where does it go? I don’t think man has ever been there. We’re under cosmic control and have been for a long longh time, and each time it builds, it’s bigger, and it’s stronger. And then you find out ... about Cosmo, and you discover that he’s running the show ... (Wolfe, Electric, 111, 112)

Literature on the bus. Yes, they do read a lot. C. G. Jung and his idea that their unconscious receives archertypical signals which make them become microcosmic parts of the whole pattern of the universe. Go and try to see the large pattern! (the tanker!) Go with the flow! Synchronicity! And Hermann Hesse’s The Journey to the East. Hesse describing in 1932 what the Pranksters will do in 1964—quote: "It was like the man had been on acid himself and was on the bus." (Wolfe, Electric, 128). But there are no lectures or seminars. There is no indulging into theories and philosophies. No teacher, no students—all of them are learning. Tuning in to the great flow. Opening their minds. Getting attuned to the principle.

Politics on the bus. The fall of 1965. The Vietnam Day Committee invite Kesey to speak at an anti-war rally at Berkeley. They want the name, they want the author. What they get is a raggamuffin American Army on a bus turned into a tank (the guns and cannons are made of wood), a big American Eagle painted on the bus, and a Ken Kesey dressed in orange wearing a Day-Glo World War I helmet. And the speech he holds is not a speech at all. It’s rather a statement. Kesey playing the harmonica and the Pranksters playing random notes on their instruments. They are doing their thing. Current phantasy. And the audience don’t understand them.

The Dead on the bus. Kesey and Garcia. Jerry Garcia used to hang out with other "lumpenbeatniks" in Palo Alto in the late 50ies. Down and out, dead-end kids. At that time Kesey lived among the intellectuals at Perry Lane, San Francisco. Perry Lane was the Stanford-Bohemian-Intellectual-Scene. Perry Lane was more like a club. Hard to get in. And, well, Jerry Garcia couldn’t get in. The middle-class wine drinkers had to throw him out when he and his friends wanted to crack one of their parties. Now, some years later, Jerry Garcia is a great guitar player and the leader of The Grateful Dead. Legend has it that one night in 1965 psychedelic, electrified rock music is born when the electrified basses and guitars of the Dead meet the flutes, horns, light machines, stroboscope (no, the strobe was not an invention of the disco-people!), and film projectors of the Pranksters in an ancient house rent by Kesey to perform his second big "Acid Test" (how many LSD can you stand without freaking out?). Jazz (named "Warlocks," the Dead played in cheap jazz joints) meets LSD. And the equipment! Quote: "all manner of tuners, amplifiers, receivers, loudspeakers, microphones, cartridges, tapes, theater horns, booms, lights, turntables, instruments, mixers, muters, servile mesochroics, whatever was on the market. The sound went down so many microphones and hooked through so many mixers and variable lags and blew up in so many amplifiers and roiled around in so many speakers and fed back down so many microphones, it came on like a chemical refinery." (Wolfe, Electric, 223)

The bus-bust (trying to outshine Tom Wolfe in terms of alliterations ...). Actually, it is a series of busts. First, Kesey makes it to the front-pages of California. Possession of Marijuana. Kesey, the leader, Kesey, the visionary, Kesey, the saviour. There is some evidence that he gave some pot to minors: 6 months on a work-farm. Second, Kesey is caught smoking Marijuana on a roof. The second offense leads to an automatic 5-year sentence. What a mess! Kesey runs off to Mexico: the fugitive in Puerto Vallarta. A few months later he reenters the U.S. at Brownsville, Texas. Lives as the fugitive for some time in San Francisco. Third, car-chase on a freeway—the cops get him. All in all he gets 90 days in jail and 6 months on the work-farm.

Off the bus. In November 67 Ken Kesey goes back to Springfield, Oregon. Neil Cassady is found dead in Mexico. Drugs and a heart-attack. The Pranksters split up. Various communes. When people come up to Springfield, paying the former chief a visit, they see the bus—it’s still there, parked beside the house.

" I am not young enough to know everything."