<

The 1950s—baseball integrates

A significant breakthrough for Latin players came in 1949 when the Cleveland Indians signed the renowned black Cuban player Minnie Miñoso. He was the first unquestionably black Latin American in the majors. Certain players with some black ancestry had played in the major leagues before Miñoso. Cuba had racial barriers to integration in its amateur baseball teams, but the Cuban League had been integrated since 1900. Thus, race had not been an issue in Cuba, where players such as Roberto Estalella and Tomás de la Cruz were considered to be mulattos. In the United States these players’ racial heritage was not recognized, as they were light-skinned and “passed” as white. Thus, Miñoso was a groundbreaker racially for the major leagues and became the first Latin American since Adolfo Luque to attain celebrity status. An exciting, charismatic player known to give his all, Miñoso was the premier Latin in the majors for most of the 1950s. His career extended until 1964, and he was brought back for promotional reasons for token appearances in 1976 and 1980, which made him a five-decade player. The New York Giants (later the San Francisco Giants), the Brooklyn Dodgers (later the Los Angeles Dodgers), the Pittsburgh Pirates, and the Chicago White Sox also fielded Latin players.

The Giants were aided in signing Latin American players by Alejandro Pompez, the owner of the Negro league New York Cubans, who had strong connections in Caribbean baseball. As the Negro leagues waned, Pompez, whose Cubans played at the Polo Grounds when the Giants were on the road, became a special Caribbean scout for the National League team. Some of the talent recruited by Pompez included Puerto Rican pitching ace Rubén Gómez, who joined the Giants in 1953. Eventually the Giants signed Puerto Rican infielders José Pagán and Julio Gotay, and in Orlando Cepeda they found a true star who reached the Hall of Fame. The White Sox’s Alfonso (“Chico”) Carrasquel (nephew to Alejandro) became the team’s permanent shortstop until 1956, when his countryman and future Hall of Famer Luis Aparicio replaced him. Other Latin shortstops in the 1950s were Cubans Guillermo Miranda, José Valdivielso, and Humberto (“Chico”) Fernández.

Cuban pitchers dominated among Latin American pitchers during the 1950s; most were players Cambria had signed for the Senators. Two of the best, Sandalio Consuegra and Miguel Fornieles, had their best seasons with the White Sox and Red Sox, respectively. Camilo Pascual and Pedro Ramos both developed into front-line pitchers in the 1960s.

The player who would be the first Latin in the Hall of Fame, Roberto Clemente, was signed by the Dodgers while he was still in Puerto Rico. Clemente ended up playing for the Pirates, where in 1955 he began his remarkable career as a hitter and outfielder whose only peer was Willie Mays. Clemente, a proud and sensitive man, did much to change the image of Latin players as happy-go-lucky, reckless base runners and free-swinging batters who cared little for their teams. A black Latin, Clemente protested racial bias against Latin players, swaying opinion by virtue of his intelligence and unparalleled skills on the field. His untimely death while on a mercy mission to earthquake-ravaged Nicaragua in 1973 transformed him from superstar to martyr and into a baseball icon. Clemente was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1973 without the required five-year wait (this waiting period has been waived for only one other inductee at Cooperstown, Yankee great Lou Gehrig).

The 1960s through the 1990s

In the 1960s the flow of Cuban baseball talent to the United States was cut off by the advent of the Castro regime. Still, those already in the minors and a few early defectors included players such as Tony Oliva, who won three batting championships; Tony Pérez, who would become a outstanding player with Cincinnati’s “Big Red Machine” (as that Reds team was known in the 1970s); Zoilo (“Zorro”) Versalles, who won a Most Valuable Player (MVP) award while with the 1965 championship Minnesota Twins;

Luis Tiant (Jr.), who had a long, distinguished career that began with the Cleveland Indians but peaked with the Red Sox and the Yankees; Cookie Rojas, an acclaimed second baseman with the Phillies; Miguel Cuéllar, winner of a Cy Young Award with the Orioles; and Bert Campaneris, a great shortstop and premier base stealer with the Oakland Athletics.

During the 1960s the number of Puerto Rican players increased, and preeminent players such as Clemente and Cepeda were reaching their peak. A Panamanian second baseman, Rod Carew, began his Hall of Fame career in 1967. In the 1960s and ’70s Carew won seven batting titles in the American League and wound up with a lifetime batting average of .328. A new development was the arrival of players from the Dominican Republic in increasing numbers. Osvaldo Virgil, an infielder with the Giants, was the first Dominican in the majors (1956), and Felipe Alou (1958), with the same team, was the second. The first Dominican star, pitcher Juan Marichal, made his debut in 1960, also with the Giants (by now in San Francisco). With Marichal, Alou and his two brothers Mateo and Jesús, and Puerto Ricans Cepeda and Pagán, the Giants of the early 1960s were a team that, like the 1945 Senators, was loaded with Latins. Other teams, mostly in the National League, followed suit. The Pirates—with Panamanian catcher Manny Sanguillén, Dominicans Manny Mota and Manny Jiménez, Puerto Rican José Pagán, and Mateo Alou—became another heavily Latin team, led by the incomparable Clemente.

Meanwhile, Rico Carty, a slugging outfielder with the Braves, became the first Dominican power hitter in the majors. By the 1970s Dominicans were nearly as numerous in the majors as Puerto Ricans, and Cubans had dwindled to a very few because Cuba remained closed. Dominican players overtook all other Latins by the 1980s and ’90s. Pitcher Joaquín Andújar, catcher Tony Peña, and hard-hitting infielder Tony Fernández became leaders in the sport. The excellence of Dominican shortstops, such as Fernández, Frank Taveras, Rafael Ramírez, Rafael Belliard, and Rafael Santana, created the impression that the Dominican Republic was the premier producer of players for that crucial position.

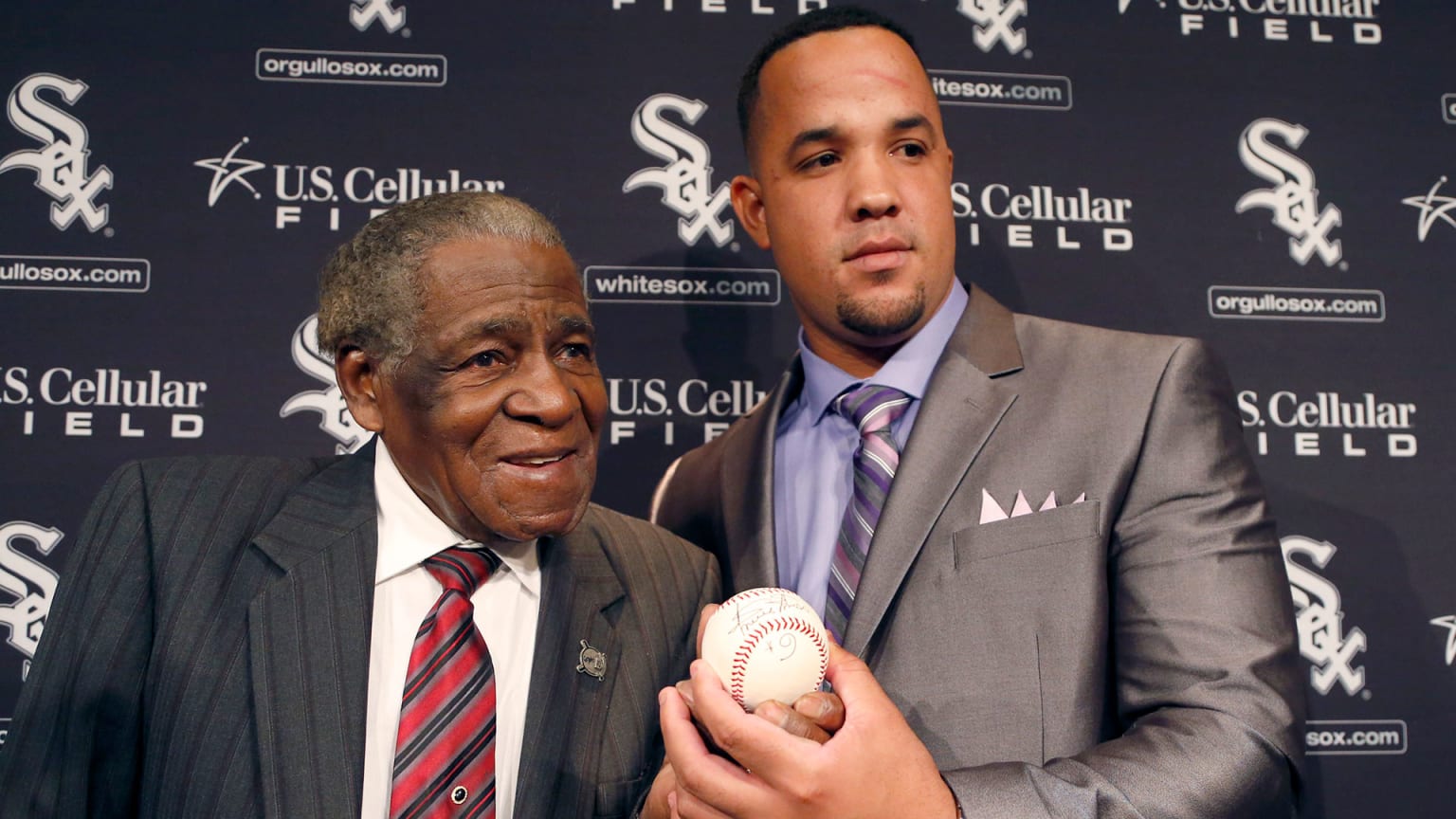

Actually, Venezuela leads in that department, going back to Carrasquel and Aparicio in the 1950s, the Reds’ David Concepción in the 1970s, and more recently the White Sox’s Ozzie Guillén and the Indians’ acrobatic wizard Omar Visquel.

The predominance of Dominicans among the Latins in the majors is due in part to the controversial—some think exploitative—baseball academies established by major league teams in that country; the summer league is also a factor in the development of Dominican talent.

The Dominican winter league continues to be a premier circuit in the Caribbean, and Dominican immigrants to the United States have also produced some excellent players, such as the Seattle Mariners’ all-star shortstop Alex Rodríguez and the Indians’ slugging outfielder Manny Ramirez. One of the brightest Dominican stars of all time, second only to Marichal, is the Cubs’ Sammy Sosa, who batted in 66 home runs in 1998 during his famed home run race with Mark McGwire.

Several outstanding players emerged in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s from Mexico, where the existence of a long-established summer league discourages many prospects from going to the United States. The most accomplished and popular of the Mexican players was left-handed pitcher Fernando Valenzuela, who had tremendous seasons with the Los Angeles Dodgers in the 1980s. Valenzuela, a charismatic player, was the only Latin player in the major leagues at that time to have a large following of his own compatriots at his home field. This situation is becoming more common, however, and the large Latin populations in several major league cities in the United States have led teams to offer Spanish-language radio and television broadcasts.

The 21st century

As the third century of professional baseball begins, the growing instability of Fidel Castro’s government in Cuba threatens to alter radically the composition of the Latin talent pool. Recent Cuban defectors such as Rey Ordóñez and Liván and Orlando (“El Duque”) Hernández are but a small sample of the wealth of players that could become available. “El Duque” has been the greatest revelation. Because of his cunning and pitching know-how, he is a throwback to Méndez, Luque, Marrero, Pascual, and Tiant, the legendary Cuban pitchers of old. But he is also a superbly conditioned athlete, the product of modern training techniques. Cuba has nearly twice the population of the Dominican Republic and a baseball tradition that goes back to the 19th century. In a very short period, Cubans could again dominate Latin baseball in the majors, though never as absolutely as they did in the 1940s and ’50s.

A sudden influx of Cuban talent to the major leagues could have an unsettling effect. Major League Baseball, the governing body of the U.S. major leagues, would need to institute a draft to regulate the flow of players from Cuba. Given the potential number of Cuban players ready to play professional baseball, the Latin presence in the majors would increase dramatically, speeding up changes that are already occurring. Major league teams already have Spanish-speaking managers and coaches throughout their systems, but their numbers would have to increase. Some of these coaches would have to act as interpreters, as former player José Cardenal did for “El Duque” Hernández during his first two years with the Yankees. Spanish coverage via radio and television will surely increase with more Latin players involved and with Latin communities, such as the one in Miami, having enough purchasing power to make a difference.

The game itself will not deviate much from the model offered by Major League Baseball. The fact that there are Latin sluggers like Sosa and Canseco and flame throwers like Armando Benítez and Mariano Rivera means the Caribbean is adapting to the game as it is played in the majors. Latin baseball was once a game of “inside baseball.” This type of baseball depends on advancing runners one base at a time via offense such as the bunt and the hit-and-run. For some time U.S. baseball has instead focused on power baseball, in which players concentrate on hitting home runs far more than on advancing a base runner with a well-hit single. Power is the foundation of the spectacle for pay, and even in communist Cuba baseball is a power game today. There is a homogenization of baseball at all levels. Even the distinctiveness of the National and American leagues is being eroded as they are subsumed under the umbrella of Major League Baseball. Umpiring has been standardized, and interleague play has been instituted. With a commissioner drawn from the ranks of the owners themselves, it is very unlikely that market forces will be thwarted by aesthetic, ethical, or political criteria, except those that benefit Major League Baseball. Having played league games in Japan, there is the possibility that Major League Baseball will become a global monopoly, with affiliated leagues throughout the world. But there is also the danger that the North American version will remain the majors and the rest of the world the minors.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Latin- ... integrates